I remember the first time I saw a Kaposi’s Sarcoma lesion in real life. I had seen photographs of the small purplish spots, the first symptom of AIDS, in the early 1980s. But in the summer of ’82, sitting on barstools with my friend Steven Fregoso at Griff’s on Melrose—a Levis, leather, and sometime cowboy bar—Steven’s friend Bob McCormack stormed in. Instead of his usual devilish smile, he approached us looking grim and scared. He pulled up to the bar saying, “Hi you guys. I’ve got it and it’s scaring the shit out of me.”

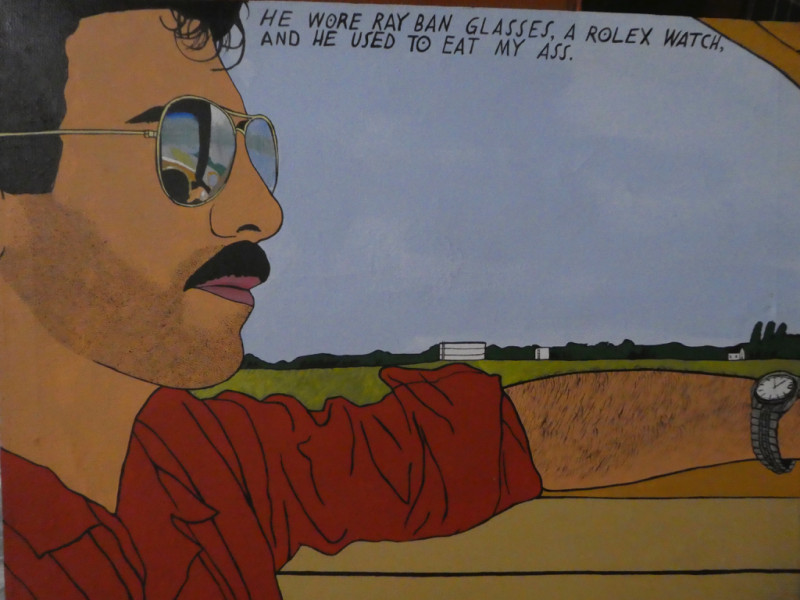

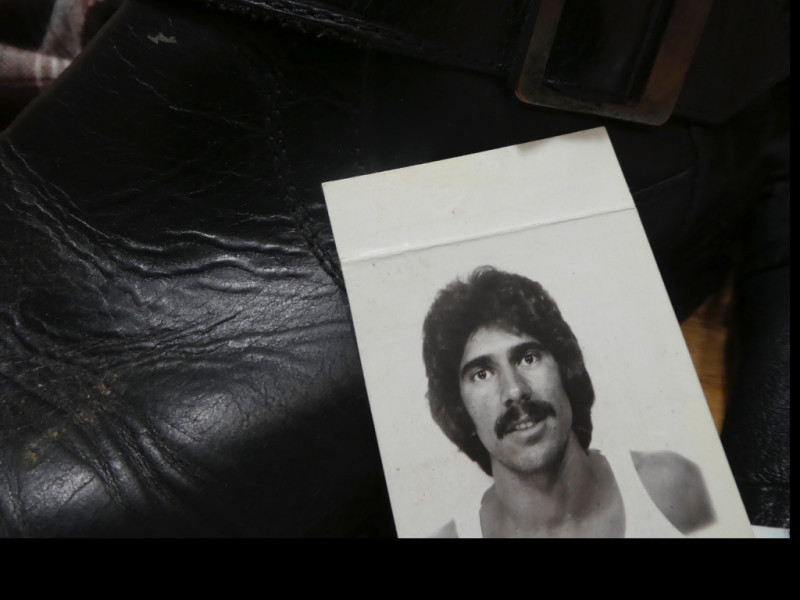

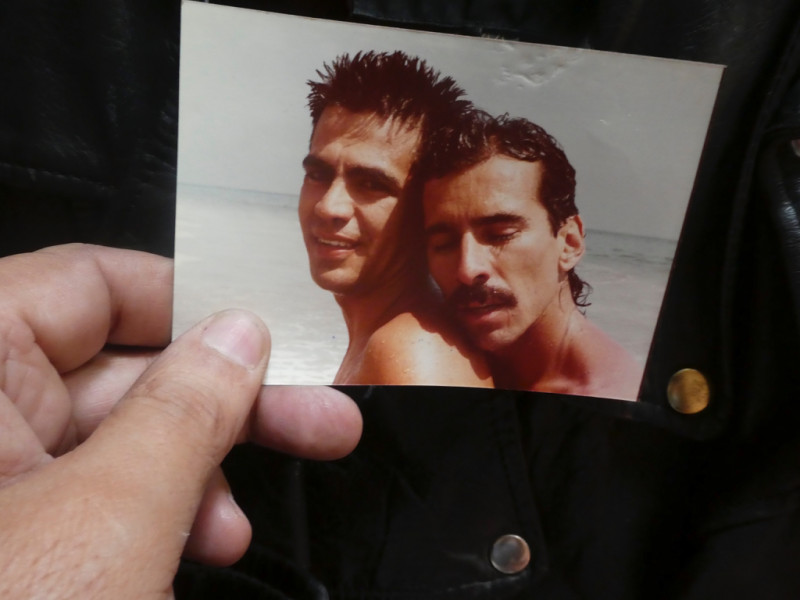

Bob usually talked fast, but now his voice was shaky. His dark blonde hair was unkempt and his handsome mustache was sweaty. Placing his left elbow on the bar, his right hand rolled down his blue plaid flannel shirtsleeve to the bend in his arm. There, on his hairy surfer-tanned forearm, was a dark blue-black velvety spot the size of a quarter. Do you know that thrill that’s a mix of fear and endorphin rush that comes when you start the downhill fast drop on a roller coaster? It also happens during the first 30 seconds or so in an earthquake, when you realize the earth is shifting like Jello beneath your feet. You feel it as a heightened sense of surprise, which some refer to as your hair standing on end. I had that rush. I inhaled an audible gasp and so did Steven.

My first inclination was to grab the bar towel and wipe Bob’s arm clean, to remove that dark quarter. But I knew the spot wasn’t going to go away. Bob was stuck. I’m not sure how one can read fear in a person’s eyes, but his blue ones were filled. He looked incredibly handsome, breathlessly continuing to talk to Steven, excited and agitated as he rolled back up his sleeve, looking around. He only showed it to us. He didn’t want anyone else in the bar to see it, but I saw it in my mind, even after his shirtsleeve was buttoned. That’s what it looks like, I thought, and it’s here in Griff’s. It’s here on Melrose.

I felt so sorry for Bob. Based on what we experienced in the early 1980s, I knew he was going to die, sooner rather than later. There was no place to run. No place to hide. My fear-driven denial kicked in, as I sat in stunned silence. Didn’t it seem like only white men were getting AIDS? Maybe it wouldn’t affect us Chicanos. Maybe Latinos would be spared, maybe? What I was ignoring was that a couple of my friends had already mysteriously started losing weight. And, unbeknownst to me at that time, I already had the virus inside me, but that’s another story. At that moment, I knew Bob was going to die. Self-righteous televangelists would stoke public fear and shame him. He was no pariah to me, but his disgrace would also come from within our own community of men, his lovers, his friends, his tricks—not all would offer support. I knew the war was coming but could not foresee the onslaught of suffering and death just around the corner. For me, the stigma of HIV and AIDS had begun.

•

It’s 2018, and some things are easier to get used to than others. My hotel room in Johannesburg is comfy and quaint, smelling of fresh linens, with a charming kitchenette, perfect for morning tea before driving out for site visits. Outside the city, on the banks of the Jukskei River, we arrive at a slum named Alexandra, but everyone calls it Alex. One of the poorest urban areas in the province of Gauteng, it continues to grow, shack by shack, built of scrap metal, sheets of tin, cardboard, and concrete blocks, right up against the river. We are here to visit a small organization, the Ntethelelo Foundation, run by a striking woman named Thokozani Ndaba. As a practitioner of applied drama and theater, she engages young girls from Alex in therapeutic drama skills and songs.

About 20 girls welcome us, singing in Zulu. They hold hands, clap, and share traditional dance moves and gestures. I am very moved by this. The storage space where they meet is filled with heavy old industrial-type stoves, rusty pipes, and metal equipment. It’s dirty, oily, dusty, and cold. And yet it’s their safe space. Standing and sitting on these industrial components, they introduce themselves to me, recite their sisterhood pledges of support for one another, eyes wide open, expressing their ambition to rise above and beyond the chaotic and dangerous surroundings where they live.

They tell stories of trauma, of having to negotiate dark pathways at night to go to the outhouse, where they are vulnerable to assault; of rape and domestic violence; of abuse from parents or family members stuck in addiction to drugs or alcohol; of gaining strength from the other girls and participating in theater, poetry, and singing. These children are beautiful and I tell them so.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the organization for which I work, as Director of Global Advocacy and Partnerships, provides Ntethelelo Foundation with funding for their programming. I express what an honor it is for me to meet them. They, in turn, are thrilled that someone from L.A. would travel so far, to come and see them. I explain that I am here to share as someone living with HIV for 38 years. For most, that is more than twice their lifetimes. Their response is total stunned silence, for one second, then two. Eyes widen, heads look up, as my words sink in. Then applause and a joyful noise echo in their safe space. I know some of the girls are HIV-positive. Some were born with the virus and others acquired HIV through sexual assault. Most all had parents or family members who died. Now, the mere thought of a Person Living with HIV, thriving for 38 years, elicits singing and laughter. We bring out a surprise cake, with ice cream, oranges, and cookies. Some girls decorate each other’s faces with white frosting, mimicking a cultural tradition of face painting. As dusk descends, we say our goodbyes and get back in our vehicle heading to our hotel.

I notice I have a phone message on one of the hook-up apps, a reply from a young man in LA with whom I had exchanged preliminary “hellos” a day earlier. He asks a three-word question, “Are you clean?” meaning, “Are you HIV-negative?” I sigh in disappointment as I look at the starry African sky, realizing I still have a lot of work to do.